Michael Rubloff

Jul 21, 2025

At The New Yorker, where tradition often defines the house style, bringing in an emerging imaging medium like 3D Gaussian Splatting isn’t as simple as installing a plugin. For Sam Wolson, the Visual Features Editor at the magazine – who has been working at the intersection of emerging technologies, documentary storytelling, and projects in VR and Photogrammetry, with the New York Times and National Geographic – the process was less about chasing a trend and more about expanding the expressive boundaries of journalism.

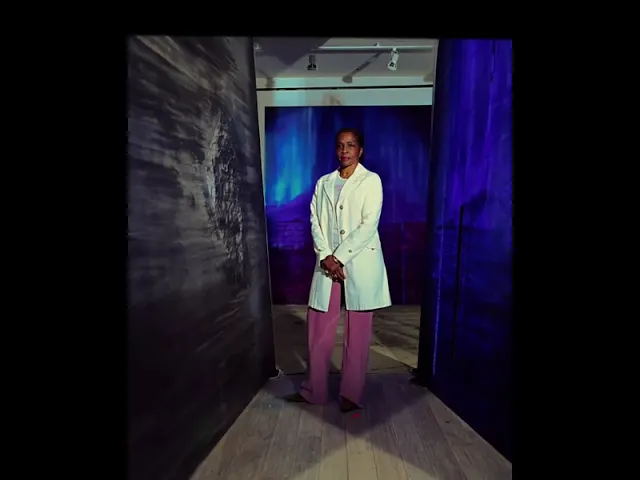

His first published project using Gaussian Splatting was a portrait of Lorna Simpson, part of the magazine’s New York-themed anniversary issue. On the surface, it’s a moment captured with elegance, simplicity, and just a hint of digital magic. But behind the scenes, Sam had introduced something entirely new: a 3D representation of a real subject, captured on set during a real world photo shoot, processed locally, and rendered in a way that gave him full control of the camera after the fact.

“It’s not necessarily about showing the audience that it’s a 3D model,” Sam said. “It’s that I can do impossible things in post. I can design how we experience this portrait in ways that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive or just technically unfeasible.”

That creative flexibility, the ability to recompose, reframe, and reveal, is just one facet of what radiance field representations like gaussian splatting enables. In the Lorna Simpson piece, the final animation was indistinguishable from video. But the storytelling advantage wasn’t visual flair. It was the fact that Sam could make new decisions after the moment had passed. In his words, it allowed him to “put her inside of a frame and break through it,” a poetic way to tie image and message together.

Like many others, Sam first encountered Gaussian Splatting through curiosity, testing mobile apps like Luma and Polycam, fiddling with open source implementations. But making the jump from personal experimentation to institutional publication meant rethinking everything from technical workflow to editorial compliance. At The New Yorker, where the fact checking department is one of the largest on staff, introducing any new tool requires explaining exactly what it does, how it works, and, most critically, why it matters.

That meant Sam not only had to show why Gaussian Splatting was valuable, but also how it sidestepped many of the concerns around AI generated media. Unlike tools that are trained on broad, scraped datasets, the splats in Sam’s workflow were constructed from entirely local image and video captures occurring in the real world using normal 2D. Postshot, the software used for training, kept everything offline and free of any legal or IP related questions.

“We had to explain to people that yes, it’s training, but it’s not AI in the generative sense,” Sam said. “It’s training on our own captured data, and the result is a reconstruction of something that was physically there.”

Sam’s early epiphany came not from a flashy effect, but from a quiet realization: Gaussian Splatting didn’t need to be flashy. It just needed to be flexible. On a typical high budget photo shoot, thousands of images might be taken to produce one final frame. With 3DGS, a few minutes of capture could yield a spatially explorable version of the scene, allowing for reimagined cinematography after the shoot wrapped. What began as an experiment on the side of a traditional assignment quickly became a foundation for more ambitious work. Sam’s next project, still in production, uses splats in an elevated way.

Sam is quick to acknowledge the paradox inherent in these tools. On one hand, radiance field representations like Gaussian Splatting bring us closer to the ground truth, capturing appearance in high fidelity, from novel views, without a need for meshing or texturing. On the other, they introduce an uncanny sense of mediation. Scenes are reconstructed, interpolated, stitched from time, not captured in a single moment, but feels remarkably like one to the viewer.

This tension becomes especially fraught in the context of journalism. What does it mean to show something that looks real, but was built from parts? Can these tools be trusted at the site of a bombing, a courtroom, or a politically sensitive location? Wolson doesn’t pretend to have the answers, but he believes in the power of careful, intentional use.

“I think what’s sacred here is the story. I’m excited about the tech, but only as a way to help someone feel what another person felt, to bring them into a moment.”

Sam’s work may still be early in the timeline of radiance field adoption, but it’s already offering a model for what’s possible and how to do it responsibly. From navigating hardware constraints (he trained his first models over Zoom on a collaborator’s personal PC) to getting internal buy-in from photography editors and legal teams, he’s built a replicable path through a landscape that can seem opaque.

Most importantly, helping to prove that Gaussian Splatting is not just a technical marvel, but rather a new visual grammar. One that, in the right hands, can enhance the act of storytelling. As tools mature, formats stabilize, and hardware catches up, the possibilities will only grow. But even now, Sam’s work stands as a precedent. A case study in how radiance fields, handled with care and intention, can help us not only see more, but feel closer to stories.

And now, with internal support earned and new projects underway, Sam is stepping more fully into that role. At a place known for its reverence for the written word, he’s quietly becoming a new kind of journalist, one equipped to tell spatial stories with authenticity, curiosity, and vision for the future.

Trending Articles

- TRENDINGLoading...

- TRENDINGLoading...

- TRENDINGLoading...