Michael Rubloff

Aug 7, 2025

“We just did it anyway,” Brenden says, half laughing. Mike is already picturing ethernet cables snaked across a London bus floor, because that is where one of their 3D captures happened. Between a fashion week scrum, a terabyte of 4D footage, and a staircase you are not allowed to fly a drone over, the pair have carved out a place for themselves in the messy birth of Gaussian Splatting as a creative medium.

Brenden comes from film and advertising, two features in 2019 and 2020, stints on high end campaigns for Montblanc, Adidas, Nike. He directs, produces, edits, whatever the job needs. Traditional CG felt slow and pricey, so the idea of scanning reality cheaply and then relighting it inside Unreal looked like a shortcut into wild visuals. Mike’s path starts in photojournalism. He wanted a way to document the world in volume, not just on a plane, so he began bolting Sony RX0 cameras to poles, then networking them. Sony once promised hundreds of those little boxes could sync perfectly; Mike decided to find out. Now he owns forty eight, runs forty seven at once off a single switch, and scripts the drudgery so Brenden can focus on the art.

They operate as a two person pipeline. Mike captures and processes, Brenden art directs and finishes. There is no optimal scenario in their stories, only problems to bulldoze. The first time they worked together, on a live music video for Quarry, they had almost no budget and twenty eight cameras in a dark room.

The next experiment came in the fashion industry with an exciting proposition, an hour alone with models, steady lights, a space to themselves. Reality was elbows, cycling color temps, shadows from every direction. They stayed anyway. Three days later an interactive scan and an edited piece landed in Vogue and across fashion blogs. That was the moment they knew they could work at the speed of a normal 2D crew and still leave with volumetric assets.

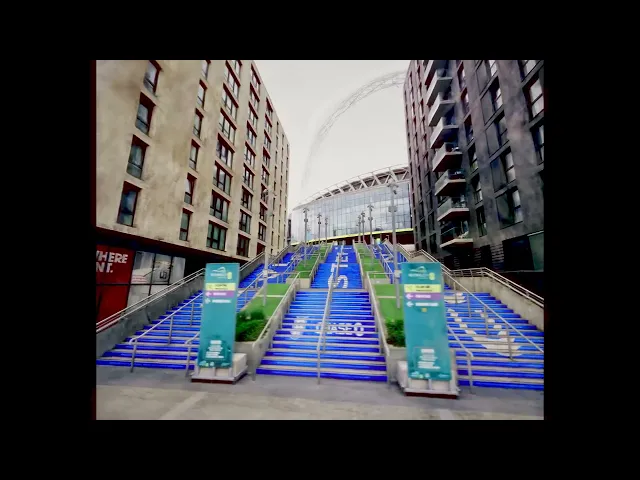

Brenden’s agency detour at We Are Social brought them to the Spanish Steps in Wembley for Chase Bank. Drones were not allowed, permissions would have taken forever, so he pitched a scan. “Mike can grab the steps, I will fly a camera in post,” he told them. A laughably low quote sailed through and was approved. Mike delivered a high fidelity splat of the famous lettered staircase. In Unreal, Brenden sent a virtual camera swooping from a vantage point no real rig could occupy. A CG build would have cost tens of thousands. They delivered on a fraction of the cost and the video made a huge impact.

Static splats are one thing. Moving ones are a different beast. For the Nick Diver music video the pair hauled forty seven synced cameras into Premises Studios in Hoxton. The band was hungover, the rig temperamental, so Mike captured at 30, 60 and 120 frames per second just in case. Two hours later he had a little over a terabyte. The plan had been a full length 4D performance playing in real time. Two weeks of processing yielded thirty seconds. They pivoted. A second round of captures used a four camera stick rig around London. Brenden wove 3D and 4D into a VR experience inside Unreal. He chose 180 degree monoscopic to stop viewers from staring in the wrong direction. It still took about thirty hours to polish thirty seconds so it ran smoothly and matched audio.

Mike keeps coming back to a simple observation: Gaussian splats behave like photographs. Shadows fall where you expect them to, light blooms, reflections register. To him splats extend photography; they do not replace it. The same goes for 4D and cinema. The point is not to mimic a single camera, it is to do what cameras cannot. Glide through a person’s face. Reveal a scene that shifts as you orbit it. Take a handheld terrestrial scan and give it the sweep of a drone. If the image could work the same way in 2D, why splat it at all?

Teaching is next. Central Saint Martins invited them to run a course after seeing the fashion work. Brenden did his master’s there, so it is a full circle moment. They plan to share some tricks and hold a few back. Students will inherit better tools, but they will still need the instincts you only get when a light rig cycles every five seconds and you do not have permission to be where you are.

As for what comes after that, Brenden keeps picturing sports. A UFC fight, a boxing match, an NFL play, captured volumetrically so you can walk around a frozen punch on an Apple Vision Pro.

Agencies will follow when they have to. The first time a creative director says “Why did we not splat this, now we need the shot we missed,” budgets will shift. When color grading a splat is as simple as dragging a ProRes clip into Resolve, pipelines will shift. When audiences expect to look around by default, interactivity stops being a novelty and turns into an expectation.

Five years from now, all this will seem obvious. Today it looks like Brenden apologizing for a bad phone angle, Mike hard cabling five cameras on a London bus, and both of them laughing about a fashion show that went completely off script. New mediums do not begin with clean tools and perfect plans. They begin with people who do it anyway.

Trending Articles

- TRENDINGLoading...

- TRENDINGLoading...

- TRENDINGLoading...